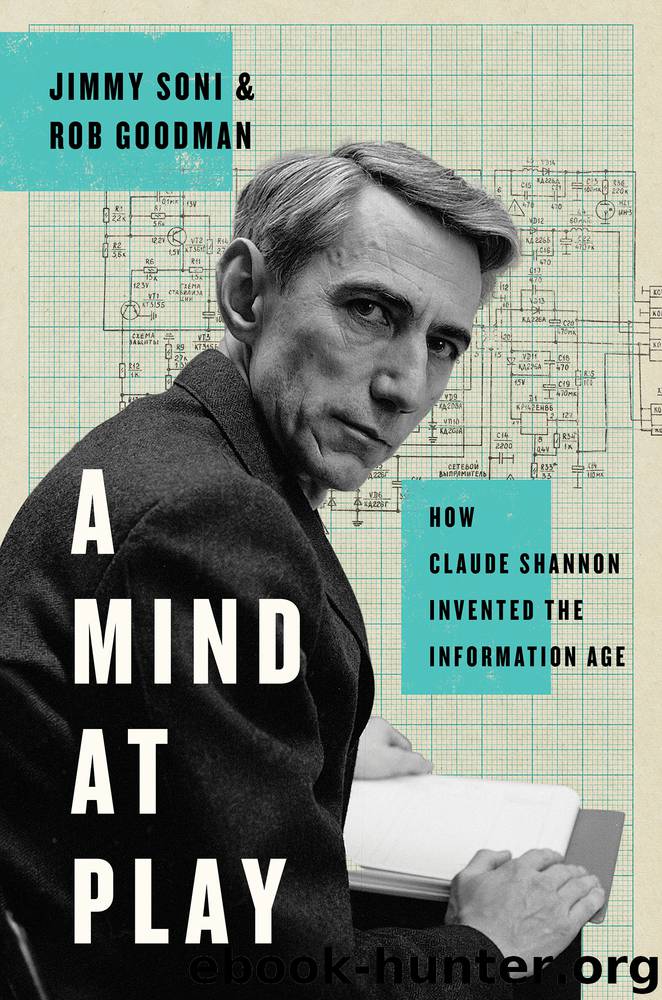

A Mind at Play by Jimmy Soni

Author:Jimmy Soni

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

* * *

Wiener’s contribution was contained within the wide-ranging book Cybernetics, which had its debut in the same year as Shannon’s two-part paper. If Shannon’s 1948 work was, at least initially, relatively unknown to the wider public, Wiener’s notion of cybernetics—a word he derived from the Greek for “steersman” to encompass “the entire field of control and communications theory, whether in the machine or in the animal”—aroused intense public interest from the moment it was published. A bestseller, the book managed to find its way into the hands of nontechnical readers. The praise was fulsome, the kind of acclaim that most authors work a lifetime to achieve. In the New York Times, the physicist John R. Platt ranked Cybernetics as one of those books that “might be comparable in ultimate importance to, say, Galileo or Malthus or Rousseau or Mill.” One of Wiener’s most ardent supporters, Gregory Bateson, called cybernetics “the biggest bite out of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge that mankind has taken in the past 2,000 years.”

Wiener must have found words like that especially gratifying in light of his efforts to position cybernetics as the era’s Theory of Everything. Few qualities set Wiener and Shannon apart more than their attitudes toward publicity. “Wiener, in a sense, did a lot to push the idea of cybernetics, which is a somewhat vague idea, and got a lot of worldwide publicity for it,” said Stanford’s Thomas Kailath. “But that wasn’t Shannon’s personality at all. Wiener loved the publicity, and Shannon could not have cared less.”

The popular success of Cybernetics launched a debate over priority within the small clique of mathematicians who wanted to know whether Wiener or Shannon could rightly claim credit for information theory. It also gave rise to a dispute over whether or not Wiener—whose chapter on information as a statistical quantity was admittedly a small section of his book—even knew what information theory meant.

Shannon’s 1948 paper, for its part, gave Wiener credit for influencing his view of the statistical nature of communication. But as more attention was paid to the field, Shannon came to realize that he differed from Wiener in some important respects. For one, Shannon insisted that meaning had nothing to do with the transmission of information, a point he believed was critical; Wiener’s view of information, on the other hand, included meaning. But perhaps the most significant distinction between their efforts is that the analysis of coding, and its power to protect information transmission from noise, is absent from Wiener’s work. Shannon, an engineer by training and inclination, attacked the problem of noise as an engineer might—and his Fundamental Theorem for a Discrete Channel with Noise is the starting point for much of the coding that makes modern information technology possible. This was the key element missing from Wiener’s work and the reason, it seems, that Wiener’s efforts to claim credit for information theory rankled many of Shannon’s followers. As Sergio Verdú, an information theorist of a later era, put it, “in fact,

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Algorithms of the Intelligent Web by Haralambos Marmanis;Dmitry Babenko(17026)

Jquery UI in Action : Master the concepts Of Jquery UI: A Step By Step Approach by ANMOL GOYAL(9754)

Test-Driven Development with Java by Alan Mellor(7747)

Data Augmentation with Python by Duc Haba(7621)

Principles of Data Fabric by Sonia Mezzetta(7392)

Learn Blender Simulations the Right Way by Stephen Pearson(7303)

Microservices with Spring Boot 3 and Spring Cloud by Magnus Larsson(7154)

Hadoop in Practice by Alex Holmes(6663)

RPA Solution Architect's Handbook by Sachin Sahgal(6526)

The Infinite Retina by Robert Scoble Irena Cronin(6228)

Big Data Analysis with Python by Ivan Marin(5952)

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(5532)

Pretrain Vision and Large Language Models in Python by Emily Webber(4912)

Infrastructure as Code for Beginners by Russ McKendrick(4666)

Functional Programming in JavaScript by Mantyla Dan(4485)

WordPress Plugin Development Cookbook by Yannick Lefebvre(4402)

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff(4264)

Embracing Microservices Design by Ovais Mehboob Ahmed Khan Nabil Siddiqui and Timothy Oleson(4158)

Applied Machine Learning for Healthcare and Life Sciences Using AWS by Ujjwal Ratan(4147)